design/policy/chicago

Cities are shaped by many factors -- geography, economics and weather, just to name a few. Urban planners, by which I mean the broad range of professionals whose job it is to change cities, have two primary means through which to wield their influence: policy and design.

I recently spent a weekend in Chicago, which is an excellent laboratory to study the different ways that policy and design can alter a metropolis. Birthplace of the skyscraper and second home of Mies van der Rohe, Chicago has always been a center of modern design. It also has a history of innovative municipal policy, and though not every experiment was a success, everything Chicago has done is influential.

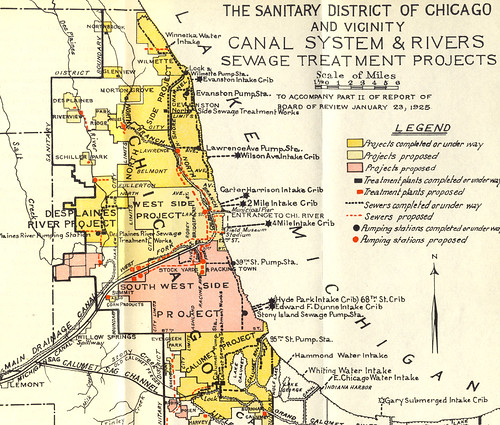

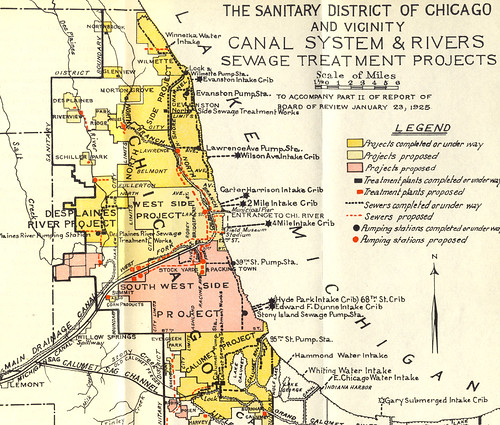

The creation of the Chicago Sanitation District is a good example of innovative policy. Signed into existence by the Illinois State Legislature in 1889, the Sanitation District was a legal entity designed to bypass the bureaucracy of the local government to provide the city's residents with safe drinking water. (For many years, sewage drained into Lake Michigan, which also happened to be the city's source of drinking water.)

With a board appointed by elected officials and the ability to sell bonds, the Sanitation District planned and financed a monumental engineering project that reversed the flow of the Chicago river in 1900. Later, it pioneered the use of chemical sewage treatment and built the world's largest drinking water purification plant.

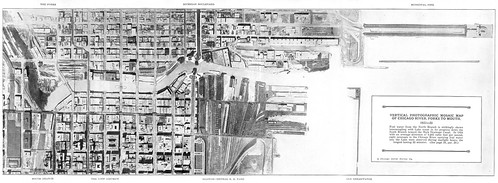

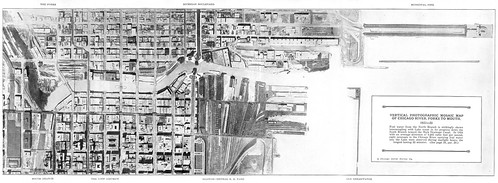

On the left edge of the photo, note the dark colored sewage in the Chicago River's North Fork being diverted from Lake Michigan.

On the left edge of the photo, note the dark colored sewage in the Chicago River's North Fork being diverted from Lake Michigan.

The Chicago Sanitation District's basic funding mechanisms and board composition have had a huge influence on structure of later regional management organizations like the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (1921) and BART, the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (1951).

On the other hand, the Cabrini Green projects epitomize the worst of 20th century American urban renewal policies. They're finally being torn down.

On the other hand, the Cabrini Green projects epitomize the worst of 20th century American urban renewal policies. They're finally being torn down.

For the most part, Chicago is flourishing today. While much of the recent success stems from national economic and cultural trends, Chicago's urban planning deserves at least partial credit. Implementing thoughtful design in harmony with innovative policies, Chicago's planners are achieving popular and sustainable goals: safer streets, greener buildings, and more engaging public spaces.

Due to a bit of policy I don't understand, Millenium Park is closed at 11:00pm. It did mean that I had the place to myself after sneaking in.

Chicago's newest design icon is 'the bean.' A key component of the recently completed Millennium Park, Anish Kapoor's ultra-reflective blob both engages the public and pays homage to the incredible skyline of its home. It somehow reduces inhibitions in its viewers -- adults spontaneously dance in its distorted reflections and strangers strike up conversation with one another. It is a remarkable example of almost pure design reshaping the public space.

Elsewhere in the city, the influence of pure policy can be seen. On virtually every street with commercial use, cafes and restaurants have moved beyond their storefronts to take advantage of a sidewalk patio ordinance that encourages businesses to use public space. It's a simple law, but it has made an amazingly broad impact, improving the pedestrian experience in business districts across the city.

In most cases, planners use a combination of policy and design to achieve civic goals -- it's not always sidewalk ordinance on the one hand and 110 tons of polished steel on the other. At its best, planning is transparent -- you have safe drinking water without thinking much about it. At its worst, planning can interfere with lives, damaging communities or forcing people from their homes. Chicago is perhaps the ideal case study for urban planners, as there is so much to learn from.

I recently spent a weekend in Chicago, which is an excellent laboratory to study the different ways that policy and design can alter a metropolis. Birthplace of the skyscraper and second home of Mies van der Rohe, Chicago has always been a center of modern design. It also has a history of innovative municipal policy, and though not every experiment was a success, everything Chicago has done is influential.

The creation of the Chicago Sanitation District is a good example of innovative policy. Signed into existence by the Illinois State Legislature in 1889, the Sanitation District was a legal entity designed to bypass the bureaucracy of the local government to provide the city's residents with safe drinking water. (For many years, sewage drained into Lake Michigan, which also happened to be the city's source of drinking water.)

With a board appointed by elected officials and the ability to sell bonds, the Sanitation District planned and financed a monumental engineering project that reversed the flow of the Chicago river in 1900. Later, it pioneered the use of chemical sewage treatment and built the world's largest drinking water purification plant.

On the left edge of the photo, note the dark colored sewage in the Chicago River's North Fork being diverted from Lake Michigan.

On the left edge of the photo, note the dark colored sewage in the Chicago River's North Fork being diverted from Lake Michigan.The Chicago Sanitation District's basic funding mechanisms and board composition have had a huge influence on structure of later regional management organizations like the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (1921) and BART, the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (1951).

On the other hand, the Cabrini Green projects epitomize the worst of 20th century American urban renewal policies. They're finally being torn down.

On the other hand, the Cabrini Green projects epitomize the worst of 20th century American urban renewal policies. They're finally being torn down.For the most part, Chicago is flourishing today. While much of the recent success stems from national economic and cultural trends, Chicago's urban planning deserves at least partial credit. Implementing thoughtful design in harmony with innovative policies, Chicago's planners are achieving popular and sustainable goals: safer streets, greener buildings, and more engaging public spaces.

Due to a bit of policy I don't understand, Millenium Park is closed at 11:00pm. It did mean that I had the place to myself after sneaking in.

Chicago's newest design icon is 'the bean.' A key component of the recently completed Millennium Park, Anish Kapoor's ultra-reflective blob both engages the public and pays homage to the incredible skyline of its home. It somehow reduces inhibitions in its viewers -- adults spontaneously dance in its distorted reflections and strangers strike up conversation with one another. It is a remarkable example of almost pure design reshaping the public space.

Elsewhere in the city, the influence of pure policy can be seen. On virtually every street with commercial use, cafes and restaurants have moved beyond their storefronts to take advantage of a sidewalk patio ordinance that encourages businesses to use public space. It's a simple law, but it has made an amazingly broad impact, improving the pedestrian experience in business districts across the city.

In most cases, planners use a combination of policy and design to achieve civic goals -- it's not always sidewalk ordinance on the one hand and 110 tons of polished steel on the other. At its best, planning is transparent -- you have safe drinking water without thinking much about it. At its worst, planning can interfere with lives, damaging communities or forcing people from their homes. Chicago is perhaps the ideal case study for urban planners, as there is so much to learn from.

3 comments:

It's fair to say the roots of many NYC "authority" entities have their roots in Chicago's "district" entities, but arguably the latter trace to the various mechanisms the robber barons used to finance the transcontinental railroads -- which it turn were based on the immobilieres (if I have the spelling correct) that the French had developed earlier

We also shape cities by management... perhaps the most important one. It is the idea that we shape our cites only though designa nd policy that I think is in many ways the limiting factor for most cities and public spaces.

You're absolutely right, management is critial to defining a city. Much as design is irrelevant unless a project is constructed, policy is irrelevant without management to execute it.

Ultimately, however, the decision to manage a city differently is a change in policy. Thus while effective (or poor) city management is a major shaper of cities, I did not consider it to be the same kind of 'tool' as design or policy.

Incidentally, Chicago is a great place to study city management as well.

Post a Comment