not so superblock

In an interview with the New York Observer several months ago, the Atlantic Yards' landscape architect Laurie Olin dismisses the common stigma against superblocks as clichéd "1960s language." His own arguments for them, however, echo the naïve idealism of planners from that very era. "If I put a street through here," he states, "[then] I have less space for people and I have more cars… When people say 'superblock'— what's wrong with what this is? Because I don't see how adding one car in here is going to make it a better space. I think space on streets is actually useless space."

The current plan for Atlantic Yards involves the demapping of several streets and the creation of a residential superblock. Site Plan via Atlantic Yards Report.

The current plan for Atlantic Yards involves the demapping of several streets and the creation of a residential superblock. Site Plan via Atlantic Yards Report.

The superblock, put very simply, is a development form larger than a traditional city block. According to civic-minded urban theorists in the mid-20th century, residents of superblocks would be liberated from cars in their everyday life, living freely as denizens of self-sufficient pedestrian communities. The scale of these superblocks, wrote Bauhaus urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, would allow them to "preserve an organic community life" in the face of automobile-based cities of the future. (The Nature of Cities, 1955.)

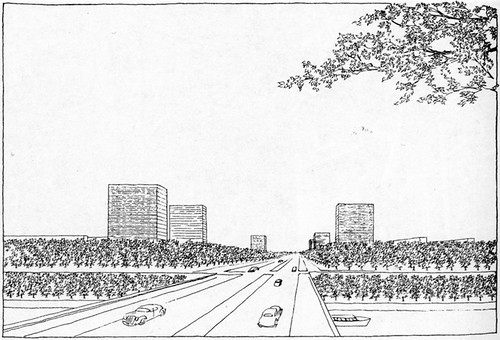

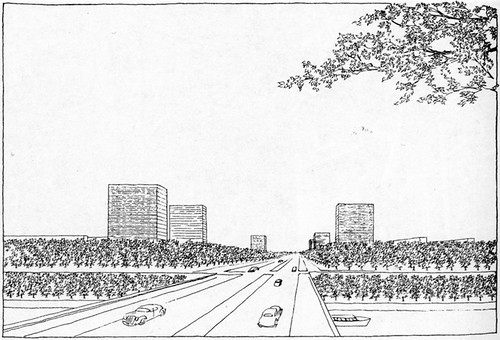

Concept for Heerstrasse and University of Berlin, 1937. Ludwig Hilberseimer. Scanned from The American City: What Works, What Doesn't by Alexander Garvin. Hilberseimer worked with Mies van der Rohe on the United States' most successful superblock project: Lafayette Park in Detroit.

Concept for Heerstrasse and University of Berlin, 1937. Ludwig Hilberseimer. Scanned from The American City: What Works, What Doesn't by Alexander Garvin. Hilberseimer worked with Mies van der Rohe on the United States' most successful superblock project: Lafayette Park in Detroit.

In practice, completed superblock projects rarely approach Hilberseimer's utopian vision: for the most part, superblock projects are boring and institutional. At worst, the designs encourage crime and neglect.

The NYU Silver Towers project north of Houston between Mercer and LaGuardia demonstrates the detrimental effect that the demapping of streets to create superblocks can have on the public realm. Despite an elegant design by I.M. Pei and a plaza with public art by Picasso, the modest superblock is a dead zone in the Village's otherwise vibrant public realm. Compared to neighboring SoHo – which has streets filled with a jumble of people and uses – the Silver Towers are a public realm failure.

NYU’s Silver Towers, a superblock created by the demapping of Wooster and Greene Streets, lacks the vitality of the smaller blocks that surround it. Photo by Hubert Steed.

NYU’s Silver Towers, a superblock created by the demapping of Wooster and Greene Streets, lacks the vitality of the smaller blocks that surround it. Photo by Hubert Steed.

With the rise of New Urbanism and the canonization of Jane Jacobs, superblocks became a sort of urban design taboo – the quintessential example of high-minded architectural theory failing in real world application. Thus of the myriad flaws in the plan for Ratner's Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn, perhaps the most surprising, from a design perspective, is its return to the superblock form. In the words of the Manhattan Institute's Julia Vitullo-Martin, "Do we not all agree with Jane Jacobs that the urbane mixtures of buildings of varying age, condition—inevitably swept away by the superblock—are a necessary condition of thriving urban life?"

Apparently not.

One dissenter, it seems, is Olin. In the past, Olin has demonstrated an incredible ability to create beautiful public space enclaves in crowded urban environments. At the Getty Center in L.A., he worked with Richard Meier to create a hilltop oasis for art; at Bryant Park, he collaborated with William Whyte to carve a cozy community park from the mind-boggling intensity of Midtown Manhattan.

Bryant Park. Photo from Forgotten NY.

Bryant Park. Photo from Forgotten NY.

Unfortunately, Olin's talents do not always translate well into projects meant to integrate into the fabric of the city, rather than stand out from it. At Canary Wharf in London – like Atlantic Yards, a mixed-use high-rise development on a post-industrial site – the public spaces planned by Olin are impersonal and lack activity. Despite crowds of people working in the area, the wharf's public spaces are often nearly deserted. (It's said that the Radiohead's Fake Plastic Trees is about Canary Wharf, even though the trees are real. For more criticism, see the Project for Public Space’s Hall of Shame.)

Canary Wharf Tube Station, London, U.K. Image from yuki*.

Canary Wharf Tube Station, London, U.K. Image from yuki*.

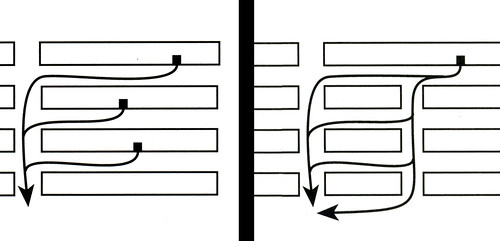

In the chapter of The Death and Life of Great American Cities entitled "The Need for Small Blocks," Jacobs bemoans the "myth that plentiful streets are 'wasteful.'" She argues that it is, in fact, large blocks that lead to wasted space by constricting "economic use [to] only where [people's] long, separated paths meet and come together in one stream." The consolidation of economic activity to confined geographic areas leads to a "depressing predominance of commercial standardization... [and] the Great Blight of Dullness." Ultimately, it is the presence of streets where things can "start up and grow" that lead to economic vitality and vibrant public space.

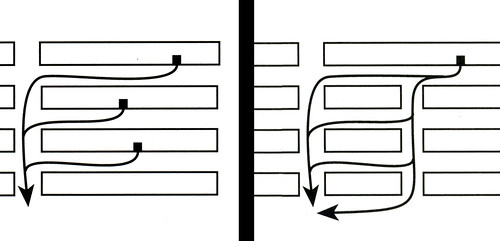

Potential pedestrian paths on large blocks (left) vs. potential pedestrian paths on short blocks (right.) From The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs.

Potential pedestrian paths on large blocks (left) vs. potential pedestrian paths on short blocks (right.) From The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs.

In his defense of the Atlantic Yards superblock, Olin ignores the lessons of Jacobs while also revealing a fundamental misunderstanding of Brooklyn's streets. In vibrant neighborhoods like those surrounding Atlantic Yards, streets are more than a means of reaching a destination: they are the destinations themselves. Besides providing a place for cars to drive, Brooklyn's streets host a diversity of restaurants, stores, and cultural institutions – all of which serve customers arriving via public transportation or on foot. Moreover, the borough often closes its avenues completely to traffic to host festivals and fairs, events that have helped to give Brooklyn the value that Ratner, the Atlantic Yards' developer, is so eager to capitalize on. By asserting that "space on streets is actually useless space," Olin demonstrates a profound ignorance regarding Brooklyn's urban form.

The Atlantic Antic, Brooklyn, NY. (This festival takes place on Atlantic Avenue -- the northern limit of the of the Atlantic Yards development.) Photo from Apollonia666.

The Atlantic Antic, Brooklyn, NY. (This festival takes place on Atlantic Avenue -- the northern limit of the of the Atlantic Yards development.) Photo from Apollonia666.

Perhaps what is most surprising about the Atlantic Yards' superblock plans isn't the designers' defense of the concept, but the support it has from its developer. Small blocks, Jacobs makes it clear, are better for business. If he knew better, Ratner would be pushing for more streets – not fewer. Indeed, the superblock is neither a pedestrian-friendly design statement nor a wise investment – it's just a mistake.

The current plan for Atlantic Yards involves the demapping of several streets and the creation of a residential superblock. Site Plan via Atlantic Yards Report.

The current plan for Atlantic Yards involves the demapping of several streets and the creation of a residential superblock. Site Plan via Atlantic Yards Report.The superblock, put very simply, is a development form larger than a traditional city block. According to civic-minded urban theorists in the mid-20th century, residents of superblocks would be liberated from cars in their everyday life, living freely as denizens of self-sufficient pedestrian communities. The scale of these superblocks, wrote Bauhaus urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, would allow them to "preserve an organic community life" in the face of automobile-based cities of the future. (The Nature of Cities, 1955.)

Concept for Heerstrasse and University of Berlin, 1937. Ludwig Hilberseimer. Scanned from The American City: What Works, What Doesn't by Alexander Garvin. Hilberseimer worked with Mies van der Rohe on the United States' most successful superblock project: Lafayette Park in Detroit.

Concept for Heerstrasse and University of Berlin, 1937. Ludwig Hilberseimer. Scanned from The American City: What Works, What Doesn't by Alexander Garvin. Hilberseimer worked with Mies van der Rohe on the United States' most successful superblock project: Lafayette Park in Detroit.In practice, completed superblock projects rarely approach Hilberseimer's utopian vision: for the most part, superblock projects are boring and institutional. At worst, the designs encourage crime and neglect.

The NYU Silver Towers project north of Houston between Mercer and LaGuardia demonstrates the detrimental effect that the demapping of streets to create superblocks can have on the public realm. Despite an elegant design by I.M. Pei and a plaza with public art by Picasso, the modest superblock is a dead zone in the Village's otherwise vibrant public realm. Compared to neighboring SoHo – which has streets filled with a jumble of people and uses – the Silver Towers are a public realm failure.

NYU’s Silver Towers, a superblock created by the demapping of Wooster and Greene Streets, lacks the vitality of the smaller blocks that surround it. Photo by Hubert Steed.

NYU’s Silver Towers, a superblock created by the demapping of Wooster and Greene Streets, lacks the vitality of the smaller blocks that surround it. Photo by Hubert Steed.With the rise of New Urbanism and the canonization of Jane Jacobs, superblocks became a sort of urban design taboo – the quintessential example of high-minded architectural theory failing in real world application. Thus of the myriad flaws in the plan for Ratner's Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn, perhaps the most surprising, from a design perspective, is its return to the superblock form. In the words of the Manhattan Institute's Julia Vitullo-Martin, "Do we not all agree with Jane Jacobs that the urbane mixtures of buildings of varying age, condition—inevitably swept away by the superblock—are a necessary condition of thriving urban life?"

Apparently not.

One dissenter, it seems, is Olin. In the past, Olin has demonstrated an incredible ability to create beautiful public space enclaves in crowded urban environments. At the Getty Center in L.A., he worked with Richard Meier to create a hilltop oasis for art; at Bryant Park, he collaborated with William Whyte to carve a cozy community park from the mind-boggling intensity of Midtown Manhattan.

Bryant Park. Photo from Forgotten NY.

Bryant Park. Photo from Forgotten NY.Unfortunately, Olin's talents do not always translate well into projects meant to integrate into the fabric of the city, rather than stand out from it. At Canary Wharf in London – like Atlantic Yards, a mixed-use high-rise development on a post-industrial site – the public spaces planned by Olin are impersonal and lack activity. Despite crowds of people working in the area, the wharf's public spaces are often nearly deserted. (It's said that the Radiohead's Fake Plastic Trees is about Canary Wharf, even though the trees are real. For more criticism, see the Project for Public Space’s Hall of Shame.)

Canary Wharf Tube Station, London, U.K. Image from yuki*.

Canary Wharf Tube Station, London, U.K. Image from yuki*. In the chapter of The Death and Life of Great American Cities entitled "The Need for Small Blocks," Jacobs bemoans the "myth that plentiful streets are 'wasteful.'" She argues that it is, in fact, large blocks that lead to wasted space by constricting "economic use [to] only where [people's] long, separated paths meet and come together in one stream." The consolidation of economic activity to confined geographic areas leads to a "depressing predominance of commercial standardization... [and] the Great Blight of Dullness." Ultimately, it is the presence of streets where things can "start up and grow" that lead to economic vitality and vibrant public space.

Potential pedestrian paths on large blocks (left) vs. potential pedestrian paths on short blocks (right.) From The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs.

Potential pedestrian paths on large blocks (left) vs. potential pedestrian paths on short blocks (right.) From The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs.In his defense of the Atlantic Yards superblock, Olin ignores the lessons of Jacobs while also revealing a fundamental misunderstanding of Brooklyn's streets. In vibrant neighborhoods like those surrounding Atlantic Yards, streets are more than a means of reaching a destination: they are the destinations themselves. Besides providing a place for cars to drive, Brooklyn's streets host a diversity of restaurants, stores, and cultural institutions – all of which serve customers arriving via public transportation or on foot. Moreover, the borough often closes its avenues completely to traffic to host festivals and fairs, events that have helped to give Brooklyn the value that Ratner, the Atlantic Yards' developer, is so eager to capitalize on. By asserting that "space on streets is actually useless space," Olin demonstrates a profound ignorance regarding Brooklyn's urban form.

The Atlantic Antic, Brooklyn, NY. (This festival takes place on Atlantic Avenue -- the northern limit of the of the Atlantic Yards development.) Photo from Apollonia666.

The Atlantic Antic, Brooklyn, NY. (This festival takes place on Atlantic Avenue -- the northern limit of the of the Atlantic Yards development.) Photo from Apollonia666.Perhaps what is most surprising about the Atlantic Yards' superblock plans isn't the designers' defense of the concept, but the support it has from its developer. Small blocks, Jacobs makes it clear, are better for business. If he knew better, Ratner would be pushing for more streets – not fewer. Indeed, the superblock is neither a pedestrian-friendly design statement nor a wise investment – it's just a mistake.